“That’s it in its dormant state,” Bill Anderson tells me as he packs away the last components of a health-club grade weights exercise station. Actually, it’s probably more professional rugby club level equipment, and is the unavoidable piece of ‘furniture’ in the room – an angular arrangement of benches, steel trusses, levers and armatures. The upright tanning pod next to it may still be eye-catchingly unusual, but the multi-gym equipment is definitely not what you’d expect to find in a first-floor, double-fronted bedroom. As he tidies the last of the weights out of the way Bill explains the rationale behind the health and fitness equipment, “A big part of all the exercises I’ve ever done all my life is to feel really appreciable benefits of focus and concentration.” Along with a strict diet regime, the exercise and ‘tanning’ equipment are part of a carefully researched network of activities designed to yield performance benefits. I’ve known Bill for almost 40 years and this all seems the logical – if slightly extreme – conclusion of his personality.

Situated in a once dilapidated terraced house in London’s Notting Hill, Bill’s workroom still feels like a work in progress. In the past, the room often doubled as a guest room or children’s playroom, but now that his children have grown up this room bears increasing signs of its colonisation by Bill’s working processes. There’s no clear structure to the arrangement of the room – no evidence of any kind of obsessive writer’s feng shui. The layout feels provisional and expedient rather than ordered – and though there’s a lot

of stuff around, everything in the room feels active: live.

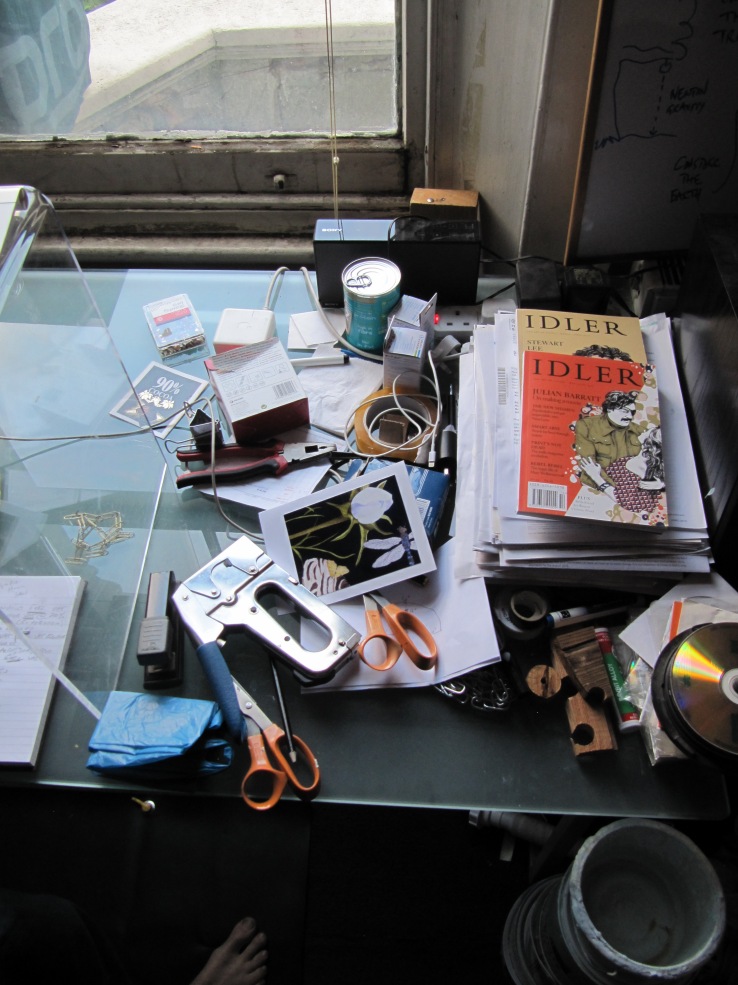

A desk in the opposite corner to the door faces out onto the gently bustling street. A laptop computer gives this area a sense of being the centre of gravity in the room. Around it – extending across the desk and beyond – are a jumble of various materials and equipment. Like the exercise kit, none of it is what you’d imagine to be standard writers’ fare.

“All these things are just stuff from other things that I do,” he says. “What tends to happen is that they encroach – they naturally encroach – and they begin to fill up the desk. I’ve got things here from a DIY project and some bee stuff (Bill is an innovative apiarist with several hives on the roof of the house and an online following)[1], and actually I really like them all being around.” This sense of the on-goingness of everything in the room is palpable. “What they’re doing for me,” he says referring to artefacts stacked on the mantelpiece from a retail project idea “is saying that ‘there’s an idea you’ve had that’s not fully realised enough’. And I think there’s something reassuring

about being surrounded by your own smell. Incomplete stuff.”

And there is a lot of stuff. I ask which of the things in the room he could do without and it invokes a mildly protective response as if I’ve suggested taking away an element of an integrated eco-system. “All these things are connected to each other. It probably in some way must connect. It must do.”

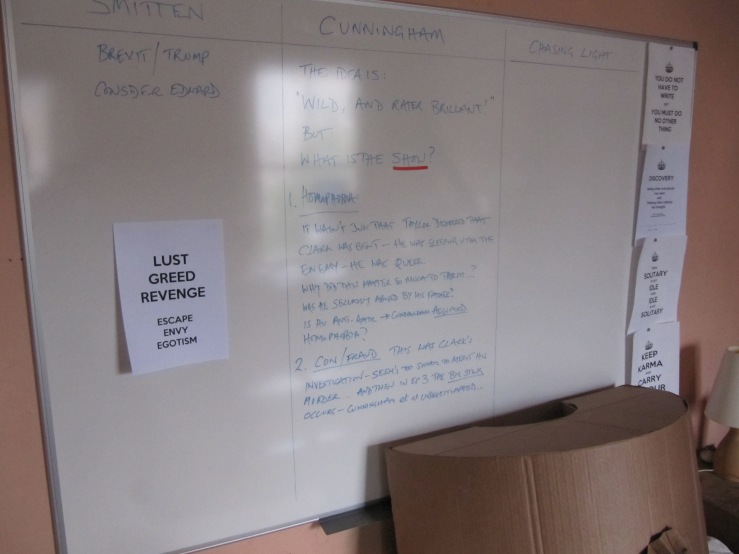

Felt-pen notes and printed out references and quotations are dotted about the room or written up on a large school-room sized whiteboard as well as on small A4 whiteboards and standard typing paper. Though they don’t offer up clear directions to an outsider it’s not too far-fetched to see these panels and sheets – with theirs names and words, lines and arrows – as like road signs. It’s an impression helped by the descriptive words Bill uses for them – ‘maps’ or ‘swim lanes’ – which suggest journeys; transit. These graphical fragments, like an expanding land survey, will often accumulate and be stuck together with Sellotape – sometimes getting pinned to the wall, sometimes lying on the floor. Whether they are addressing ideas on a project scale, or concerned with small detail, they are an important precursor to writing. Some writers go searching for their story or characters through the activity of writing, but for Bill there’s no point in beginning to write in a session until the destination is identified. The incomplete is a motivator.

He points at one area of the large whiteboard on the wall which is divided into three columns under project headings. “This is a thing that I’m working on and I’m not ready to  change that yet – I haven’t had a significant enough departure. But this thing here, there’s a big blank space there. I’m not working on that but I quite like there being a big fucking blank space up there because it makes me feel bad.” He uses the term ‘vacuum’ to describe this empty space more than once – not in a lifeless way, but as a challenge: a vacuum, after all, will draw in oxygen when it’s unpicked, unsealed. There’s little evidence around the room of the tools or resources Bill uses to achieve this; there are very few images or references around the room that have not been generated by Bill. Oxygen for Bill is not sought in the work of others.

change that yet – I haven’t had a significant enough departure. But this thing here, there’s a big blank space there. I’m not working on that but I quite like there being a big fucking blank space up there because it makes me feel bad.” He uses the term ‘vacuum’ to describe this empty space more than once – not in a lifeless way, but as a challenge: a vacuum, after all, will draw in oxygen when it’s unpicked, unsealed. There’s little evidence around the room of the tools or resources Bill uses to achieve this; there are very few images or references around the room that have not been generated by Bill. Oxygen for Bill is not sought in the work of others.

When I quiz him on sources there’s no sense of a need to keep up with screenings at BAFTA[2] or to attend professional development sessions or even to read contemporary fiction or drama to keep up with trends. What is a constant source of inspiration are facts – often with a scientific basis or methodology – about how the world works. I’ve learnt over the years not to be surprised that Bill’s latest buzz would come from the New Scientist[3] magazine rather than say, the BFI’s Sight & Sound[4] journal. With the rise of the world-wide-web, his indispensable source of information now, is the internet. “I have this thing of ‘6 clicks’” he says, suddenly passionate, “that, after six clicks on links of curiosity you’ll find something outstanding that you feel really strongly about – and that’ll have more bang for your bucks than from BAFTA.” There’s a hint that the internet also ends up being used as a search engine to discover his own hidden priorities. “Following your nose on the internet reveals your own thing to you.”

the internet reveals your own thing to you.”

If it’s not the engine driving the ‘stuff’ in the room and the creative writing, the internet is certainly vital fuel. It’s also perhaps a problem.

Anyone who has clicked through stimulating material can quickly find they’ve strayed into the territory of distraction or even – the curse of the creative – ‘displacement activity’. Six clicks might be a maximum required to find something personally interesting, but it’s almost certainly below the minimum possible in any encounter with a computer. Glancing around the room you become aware of efforts to keep the siren call of all his encroaching ‘stuff’ – and the next ‘click’ – at bay. Punctuating the space visually are printed-out mnemonics, invocations, and rules of work. These remind me of what psychologists call the ‘Ulysses Pact’[5] – a deal made with oneself to avoid changing course for a future temptation and named after the hero of Homer’s Odyssey[6]. So, just as Ulysses lashed himself to the mast of his ship to prevent himself steering towards the hypnotic and destructive call of the Sirens, Bill’s writing days are broken up into chunks of work by time tied to set goals, latent censures and scheduled rewards. It’s not hard to read self-discipline as the refuge of the tempted.

Two hours for Bill is an optimal time to work at something, especially in its early stages. More time often has diminishing returns he tells me, or can even be counterproductive when good work is undone by fading concentration. The motivational notes, though, suggest that even the desire to crack a vacuum or to find the route to a destination on a map may not be enough. He points to a favourite printed out commandment – word-processed, not hand written, as if to fortify the pact – by the American short-story writer Raymond Carver[7] which is pinned to the wall on an A4 sheet near the whiteboard. “I like this,” he says, as we talk about the day-to-day routine of writing for a project. “This is Carver’s two rules for the period you’ve set yourself to do some writing. So, you’ve said ‘I’m going to write for two hours’ and during that two hours: one, you don’t have to write anything; but, the second one is – you can’t do anything else. You can’t leave. You can’t even arrange your pencils.”

leave. You can’t even arrange your pencils.”

As a backup Bill has computer programmes that ‘lock-out’ the internet for blocks of time. “I don’t always do it but sometimes I say, ‘I’m going to do the Raymond Carver’ and remove internet access from all my devices for a period – and then even the possibility of disciplined research is curtailed. You’re just literally doing nothing else but write.”

Writing isn’t a round-the-year activity (Bill’s main bread-winning occupation is as a director of TV drama[8]) but it is a sufficient part of his self-description, his creative DNA, that he has a thoroughly worked out and practised writing regime, so that when a writing job comes along or he is preparing a script for a pitch he knows exactly what resources he wants around him and a plan of how he will use his time.

The first thing you notice about Bill’s laptop is its elevated position, propped up on a perspex cradle so that the keyboard is at a comfortable height to work on while standing up (Bill was quick to adopt the research espousing the benefits of an upright working posture). On the floor is an Earthing Mat – another performance and wellbeing device designed to mitigate the effects of our built environment – on which Bill works barefoot. All of these aids, along with the bursts of exercise, are integrated into the writing routine and all are designed to provide what modern sports’ coaches would recognise as ‘incremental gains’.

The evolving whiteboard notes and maps act as ideas updates and these will sometimes draw on audio ‘notes’ created on a smartphone by dictating (perhaps while walking the dog) into a voice-to-text app and then retrieving them from a ‘cloud’ folder on his laptop. “The software transcriptions are terrible but they make sense as reminders and they can be dragged and clicked”, Bill says, and they’re part of a continuous process of “ruminating”, as he puts it, “of logging stuff in,” that is then unpacked in writing sessions.

Bill isn’t a touch typist but decades of practice means he types faster than the ideas come. “Put it this way, it isn’t my typing that slows me down.” If he’s stuck with some aspect of the writing he is so aware of the pitfalls of displacement activity that he gets no pleasure from them. So, sticking to the task is the only satisfactory release. “If I think I’ll just make a cup of coffee because that’ll make me feel better, I know from experience that it won’t and that I’ll still have the problem afterwards.” I spot an acoustic guitar resting against an armchair. Displacement? “Actually, the guitar is usually a celebration.” Bill will pick up the guitar every day – “at least twice a day” – and will play songs that he knows, or try to figure out how to play songs that he doesn’t.

Bill will pick up the guitar every day – “at least twice a day” – and will play songs that he knows, or try to figure out how to play songs that he doesn’t.

Once a writing project is working the two hours rule can go out the window. It becomes a ‘whatever’ length of time and can involve skipping meals. Once this stage is achieved – a state of flow, perhaps; a surge towards the destination – the need to cut off the other ‘stuff’ through ‘lock-out’ apps and structured discipline becomes unnecessary.

It’s impossible not to read the room as a kind of externalised consciousness. The thinking that goes into the objects around the room: the writing; the DIY and the bee-keeping; the prep for directing? They probably in some way connect. They must do.

I’m suddenly reminded of what I’m sure is a minor pet subject of Bill’s – the hidden mysteries of fungus. A quick search (2 clicks) and I have the details I want – Mycelium[9]. Mycelium are the thread-like structures that spread invisibly underground, sometimes across huge areas, and constitute the main body of a fungus. Mushrooms and toadstools are only really analogous (ish) to the flowering part of plants. The Mycelium feeds off matter above ground and in doing this enriches the soil paving the way for even richer plant growth. Its properties are only now being fully understood and new research suggests mycelium might even communicate warnings of encroaching disease to healthy plants, triggering their defences and protecting the whole eco-system. As a metaphor it’s an especially good fit for Bill’s workplace; things that seem disparate connect themselves by invisible threads of thought.

They must do.

GJ Oct.2017

[1] https://idler.co.uk/product/the-guide-to-idle-beekeeping-with-bill-anderson-part-one/

[3] https://www.newscientist.com/

[4] http://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ulysses_pact

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Odyssey

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raymond_Carver

[8] http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0006624/

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mycelium